OncoCUP Dx – Cancer Unknown Primary Diagnosis Test

Overview

OncoCUP Dx is an innovative, non-invasive, accurate, and cost-effective already validated test for Cancer of Unknown Primary diagnosis, with potentially uses for screening, prognosis and recurrence monitoring.

OncoCUP Dx is based on a score calculation that it is obtained from several Biomarkers of the patient (mainly Tumor Markers but also patient’s clinical information).

Click here to download the brochure in PDF format.

Tumor Markers

Tumor Markers are parameters released by tumor cells, which enter the bloodstream or other biological fluids and are useful for the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment monitoring.

Most Tumor Markers are not specific to any type of cancer and the differences between benign and malignant diseases are quantitative (for example, patients with epithelial tumors tend to have significantly higher levels of these Tumor Markers than patients without malignancy).

There are now more than 20 well known parameters that are widely regarded as Tumor Markers such as PSA ―related to Prostate Cancer―, CA 15.3 ―related to Breast Cancer―, CA 125 and HE4 ―both related to Ovarian Cancer―, CEA and CA 19.9 ―both related to different gastrointestinal cancers (Colorectal, Gastric and Pancreatic Cancer)―, or NSE and ProGRP ―both related to in Lung Cancer―.

However, there are a variety of factors that can affect the accuracy of Tumor Markers by increasing its levels without malignancy presence. The main reason are benign diseases, among others, such as technical interferences.

In this sense, the Spanish Society of Clinical Biochemistry and Molecular Pathology, Cancer Biomarker Commission established the Barcelona Criteria, 4 criteria that help to correctly distinguish and value Tumor Markers results and reduce False Positives (FP):

- Tumor Markers Serum concentrations.

- Discard benign pathology by the exclusion of main source False Positive results.

- Follow-up if Tumor Markers moderate results (Grey Zone/Undetermined).

- Technical interference.

Statistical measurements in diagnostic tests

Unfortunately, the use of Tumor Markers in routine presents also other problems such as low Sensitivity in early stages, or nonexistence of any specific Tumor Marker for each malignant tumor. However, the combination of 2 or more Tumor Markers has a better outcome, especially in advanced stages.

In this regard, the combination of several Tumor Markers ―as well as the inclusion of patient history information in the equations―, using complex algorithms with multiple variables, results in higher Sensitivity and Specificity: that is what we have christened Multi-Biomarker Disease Activity Algorithm (MBDAA).

The Sensitivity of a diagnostic test is the percentage of actual positives that are correctly identified, and Specificity is the proportion of true negatives that are correctly classified. Both variables are closely linked together and give an idea of the accuracy of a test.

A test that correctly identifies all true positive as positive, but has many false negatives would have a Sensitivity of 100%, but low Specificity. For example, Sensitivity measures the number of cancerous tumors that are correctly identified as cancerous, whereas Specificity measures how many benign tumors are correctly identified as benign. A high Sensitivity means fewer cancers diagnosed as benign and high Specificity means fewer benign tumors diagnosed as cancerous.

Besides, the positive predictive value (PPV) is the number of true positives correctly identified on total real positive. A test with many false positives will have a low VPP. Moreover, the negative predictive value (NPV) is the number of true negatives correctly identified on the total actual negative. A high NPV value means that very few true positives were incorrectly identified as negative.

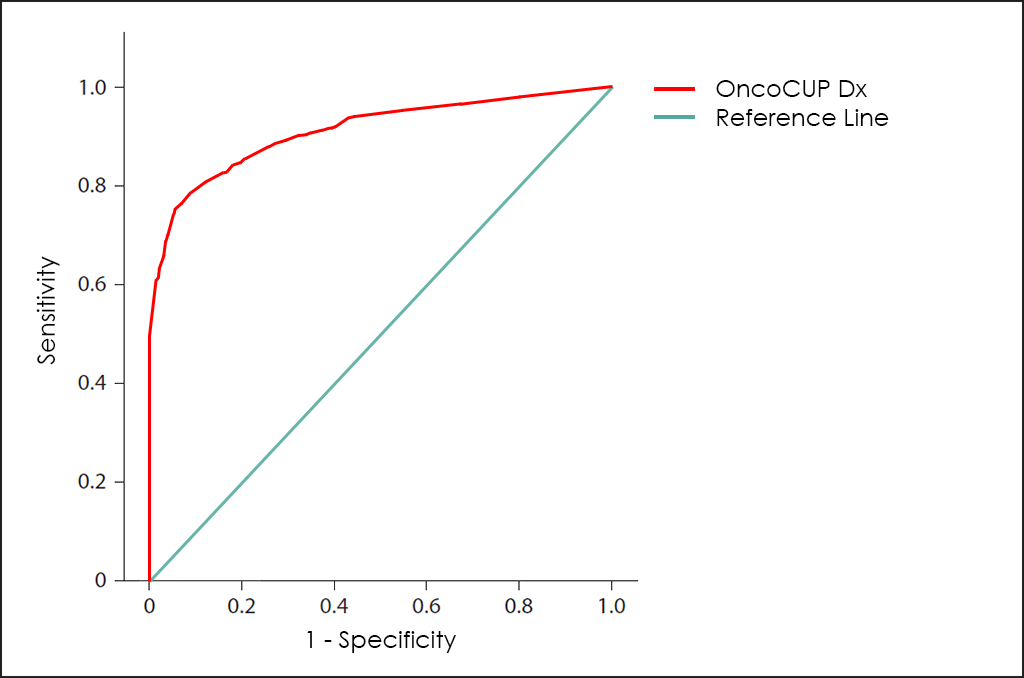

All these different values can be plotted together in a graphic that it is known as Receiving Operator Curve (ROC), where better results are displayed with curves that tends to come near to the upper left corner of the image (where 100% Sensitivity and 100% Specificity are reached).

Receiving Operator Curves (ROC)

The ROC curve of OncoCUP Dx test ―based on the combined count of AFP, β-hCG, CA 15.3, CA 19.9, CA 72.4, CA 125, CEA, CYFRA 21-1, HE4, NSE, ProGRP, PSA, fPSA, SCC and S100 Tumor Markers; comorbidities; and other data from 5.456 consecutive patients, then fine-tuned by other research―, throws really interesting diagnostic capabilities: 82.4% Sensitivity and 98.1% Specificity.

How does it work

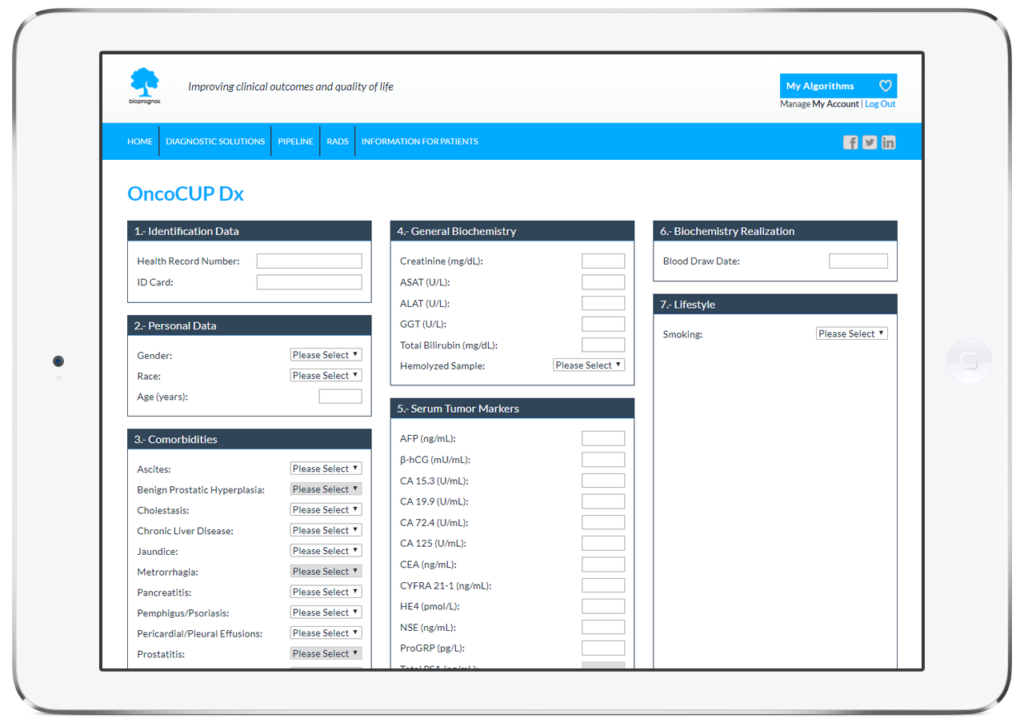

As all BIOPROGNOS’ MBDAA tests, OncoCUP Dx test is available online once access is granted through our secure Cloud Platform. As a Cloud solution, it is designed to be used in a Software as a Service (SaaS) basis, that means, no installation, no periodically patch upgrades, low TCO (Total Cost of Ownership) and no maintenance.

In this way, doctors or lab technicians only should fill the form with values obtained previously from patients (personal data, menopausal status, comorbidities, biochemistry values, medications, prior procedures and lifestyle information), and click on Submit button in order to obtain the risk score of having Cancer.

Order Form

To facilitate work, doctors can download and fill the Order Form for OncoCUP Dx in a quick and an easy way ―with all required data for a best risk calculation already detailed―.

Click here to download the OncoCUP Dx Order Form in PDF format.

Final Report

After doctors entered the patient’s data, OncoCUP Dx test presents the results in a separate screen that can be converted to a PDF document in order to be downloaded or sent by email.

Click here to download the report in PDF format.

The report includes two main sections: Patient Information and Outcome. In the first one, all patient data entered previously is showed as record. The second one includes: Results, indicating whether Tumor Marker levels are within normal range or not; Risk, with a score bar showing the probability of having Cancer; Comments, that are created dynamically to help doctors and healthcare professionals to understand ―in an easy way―, how to detect False Positives (FP), such as levels of Tumor Markers that would suspect the presence of Cancer, but when considering other variables together ―Gender, Race, Age, Comorbidities information or Smoking Habits―, do not correspond with malignant diseases; and finally, Conclusions, with recommendations suggesting to retest patient in 1 year (for Low Risk), or in 4 weeks (for Moderate Risk, that is, these cases in which Tumor Marker levels are higher than normality but there is not quite clear to be High Risk.

Please note that final report is oriented to healthcare professionals only ―not to patients―, because it was designed as “a tool to help healthcare professionals in Cancer diagnostic”, and in this way it is been certified by obtaining the CE DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY (Medical Device Directive 93/42/EEC, Class I, rule 12).

CE Declaration of Conformity

Since May 17th, 2017 (when version 1.0 was released), OncoCUP Dx test has the CE Declaration of Conformity that certifies it has been assessed to meet high safety, health, and environmental protection requirements.

Click here to download the OncoCUP Dx CE DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY in PDF format.

This declaration also certifies that OncoLUNG test can be sold throughout the European Economic Area (EEA) without restrictions.

Besides, there are two main benefits CE marking brings to businesses and consumers within the EEA:

- Businesses know that products bearing the CE marking can be traded in the EEA.

- Consumers enjoy the same level of health, safety, and environmental protection throughout the entire EEA.

Uses and purposes for OncoCUP Dx

OncoCUP Dx test has been developed for:

- Confirm or discard malignancy from results obtained previously with other tests, such as Computed Tomography (CT) Scan or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) findings thanks higher Sensitivity and Specificity than imaging procedures.

- Help doctors predict the cancer’s behaviour and response to treatment, as well as a person’s chance of recovery.

- Guide treatment decisions (such as decide whether to add or immunotherapy after surgery and/or radiation therapy), therapy monitoring (doctors may use changes in the presence or amount of one or more Tumor Markers to assess how the cancer is responding to treatment) and predict or monitor for recurrence (looking for changes in the amount of a Tumor Marker may be part of their follow-up care plan and may help detect a recurrence sooner than other methods).

The Science Behind OncoCUP Dx

Based on Publications

- Bayo J., Castaño M. A., Rivera F. and Navarro F. (2017). “Analysis of blood markers for early breast cancer diagnosis”. Clin Transl Oncol. Springer. DOI: 10.1007/s12094-017-1731-1

- Best J., Bilgi H., Heider D., Schotten C., Manka P., Bedreli S., Gorray M., Ertle J., van Grunsven L. A. and Dechêne A., “The GALAD scoring algorithm based on AFP, AFP-L3 and DCP significantly improves detection of BCLC Early Stage”. Georg Thieme Verlag KG. DOI: 10.1055/s-0042-119529

- Reichl P., Fang M., Starlinger P., Staufer K., Nenutil R., Muller P., Greplova K., Valik D., Dooley S., Brostjan C., Gruenberger T., Shen J., Man K., Trauner M., Yu J., Fang Gao C. and Mikulits W. “Multicenter analysis of soluble Axl reveals diagnostic value for very early stage HCC”. Int. J. Cancer: 137, 385–394 (2015) VC 2014 UICC. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.29394

- Molina, R., Marrades R. M., Auge J. M., Escudero J. M., Vinolas N., Reguart N., Ramirez J., Filella X., Molins L. and Agusti A. (2016). “Assessment of a Combined Panel of Six Serum Tumor Markers for Lung Cancer.” Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193(4): 427-437. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0603OC

- Molina, R., Auge J. M., Escudero J. M., Filella X., Foj, L., Torné A., Lejarcegui J., Pahisa J. “HE4 a novel tumour marker for ovarian cancer: comparison with CA 125 and ROMA algorithm in patients with gynaecological diseases.” Tumour Biol, 2011. 32(6): p. 1087-95. PMCID: PMC3195682

- Santotoribio J.D., Garcia-de la Torre A., Cañavate-Solano C., Arce-Matute F., Sanchez-del Pino M.J., Perez-Ramos S. “Cancer antigens 19.9 and 125 as tumor markers in patients with mucinous ovarian tumors.” EJGO European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. PMID: 27048105

- Shaikh N. A., Memon F., Samo R. P. “Tumor markers; efficacy of CA-125, CEA, AFP and Beta-HCG. An institutional based descriptive & prospective study in diagnosis of ovarian malignancy.” Professional Med J 2014;21(4):621-627. PDF

- Sørensen S. S., Mosgaard B. J. “Combination of CA 125 and CEA can improve ovarian cancer diagnosis.” DANISH MEDICAL BULLETIN. Dan Med Bul 2011;58(11):A4331. November 2011. PDF

- Salami S. S., Schmidt F., Laxman B., Regan M. M., Rickman D. S., Scherr D., Bueti G., Siddiqui J., Tomlins S. A., Wei J. T., Chinnaiyan A, Rubin M. A., Sanda M. G. “Combining Urinary Detection of TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 with Serum PSA to Predict Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer.” Urol Oncol. 2013 July ; 31(5): 566–571. DOI: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.04.001

- Molina, R., Bosch X., Auge J. M., Filella X., Escudero J. M., Molina V., Sole M. and Lopez-Soto A. (2012). “Utility of serum tumor markers as an aid in the differential diagnosis of patients with clinical suspicion of cancer and in patients with cancer of unknown primary site.” Tumour Biol 33(2): 463-474. DOI: 10.1007/s13277-011-0275-1

- Trapé, J. and Molina R. (2006). “Aspectos generales de los marcadores tumorales.” JANO 1620: 45-48. PDF

- Molina R., Filella X., Trapé J., Augé J. M., Barco A., Cañizares F., Colomer A., Fernandez A., Gaspar M. J., Martinez-Peinado A., Pérez L., Sánchez M., Escudero J. M. (2013). “Principales causas de falsos positivos en los resultados de marcadores tumorales en suero.” Sociedad Española de Bioquímica Clínica y Patología Molecular. Comisión de Marcadores Biológicos del Cáncer. PDF

Related Publications

- Abdelmoniem S, Zaki E, Imam H, Badrawy H, Ali S, Maximous D. Diagnostic value of a panel of tumor markers as a part of a diagnostic work-up for ascites of unknown etiology – Open Journal of Gastroenterology – 2012. DOI: 10.4236/ojgas.2012.23020

- Briasoulis E, Pavlidis N. Cancer of Unknown Primary Origin. Department of Medicine/Oncology Unit, Ioannina University Hospital, Ioannina, Greece. The Oncologist 1997;2:142-152. DOI: 10.1.1.484.4291

- Duffy, M. J. (2010). “Clinical Utility of Tumor Markers: What the Guidelines Recommend.” Journal of Laboratory Diagnostics 46(3): 281-291. PDF

- Duffy, M. J. and P. McGing (2010). Guidelines for the use of Tumour Markers. PDF

- Fizazi K, Greco F, Pavlidis N, Daugaard G, Oien K, Pentheroudakis G. Cancers of unknown primary site: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up – Annals of Oncology – 2015. DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdv305

- Furrukh M, Burney I.Cancer of Unknown Primary Site: Not All is Lost! JBR Journal of Clinical Diagnosis and Research – 2015. DOI: 10.4172/2376-0311.1000115

- Hemminki K, Bevier M, Hemminki A, Sundquist J. Survival in cancer of unknown primary site: population-based analysis by site and histology. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(7):1854-63. PMID: 22115926

- Hemminki K, Ji J, Sundquist J, Shu X. Familial risks in cancer of unknown primary: tracking the primary sites. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(4):435-40. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5614

- Mayeux, R. (2004). “Biomarkers: potential uses and limitations.” NeuroRx 1(2): 182-188. DOI: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.182

- Medicine, T. A. f. c. B. L. (2013). RECOMMENDATIONS AS A RESULT OF THE ACB NATIONAL AUDIT ON TUMOUR MARKER SERVICE PROVISION. PDF

- NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 104. Diagnosis and management of metastatic malignant disease of unknown primary origin. Clinical Guideline. Evidence Review. National Collaborating Centre for Cancer (UK); 2010 Jul. PMID: 22259823

- Novakovic, S. (2004). “Tumor markers in clinical oncology.” Radiology and Oncology 38(2). PDF

- Perez, E. O. and M. I. Aceituno Azaustre (2014). “Utilidad clínica de los marcadores tumorales.” Revista Médica de Jaén(4): 2-12. PDF

- Perkins, G. L., E. D. Slater, G. K. Sanders and J. G. Prichard (2003). “Serum Tumor Markers.” American Family Physician 68(6): 1075 – 1082. PDF

- Sharma, S. (2009). “Tumor markers in clinical practice: General principles and guidelines.” Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 30(1): 1-8. PMCID: PMC2902207

- Stieber, P., R. Hatz, S. Holdenrieder, R. Molina, M. Nap, J. von Pawel, A. Schalhorn, J. Schneider and K. Yamaguchi (2006). Practice Guidelines And Recommendations For Use Of Tumor Markers In The Clinic. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Guidelines for the use of tumor markers in Lung Cancer. PDF

- Sturgeon, C. (2002). “Practice guidelines for tumor marker use in the clinic.” Clin Chem 48(8): 1151-1159. PMID: 12142367

- Sturgeon, C. M., E. P. Diamandis, B. R. Hoffman, D. W. Chan, S. L. Ch’ng, E. Hammond, D. F. Hayes, L. A. Liotta, E. F. Petricoin, M. Schmitt, O. J. Semmes, G. Söletormos and E. van der Merwe (2009). National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines for use of tumor markers in clinical practice: quality requirements. DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.094144

- Sturgeon, C. M., M. J. Duffy, B. R. Hoffman, R. Lamerz, H. A. Fritsche, K. Gaarenstroom, J. M. G. Bonfrer, T. Ecke, H. B. Grossman, P. Hayes, R.-T. Hoffmann, S. P. Lerner, F. Lohe, J. Louhimo, I. Sawczuk, K. Taketa and E. P. Diamandis (2010). USE OF TUMOR MARKERS IN LIVER, BLADDER, CERVICAL, AND GASTRIC CANCERS, The National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry. PDF

- Sturgeon, C. M., B. R. Hoffman, D. W. Chan, S. L. Ch’ng, E. Hammond, D. F. Hayes, L. A. Liotta, E. F. Petricoin, M. Schmitt, O. J. Semmes, G. Soletormos, E. van der Merwe, E. P. Diamandis and B. National Academy of Clinical (2008). “National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines for use of tumor markers in clinical practice: quality requirements.” Clin Chem 54(8): e1-e10. DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.094144

- Trape, J., G. Gurt, J. Franquesa, J. Montesinos, A. Arnau, M. Sala, F. Sant, E. Casado, J. M. Ordeig, C. Bergos, F. Vida, P. Sort, A. Isava, M. Gonzalez and R. Molina (2015). “Diagnostic Accuracy of Tumor Markers CYFRA21-1 and CA125 in the Differential Diagnosis of Ascites.” Anticancer Res 35(10): 5655-5660. PMID: 26408739

- Trape, J., R. Molina, F. Sant, J. Montesinos, A. Arnau, J. Franquesa, R. Blavia, E. Martin, E. Marquilles, D. Perich, C. Perez, J. M. Roca, M. Domenech, J. Lopez and J. M. Badal (2012). “Diagnostic accuracy of tumour markers in serous effusions: a validation study.” Tumour Biol 33(5): 1661-1668. DOI: 10.1007/s13277-012-0422-3

- Trapé Pujol, J. and R. Molina Porto (2006). “Aspectos generales de los marcadores tumorales.” JANO 1620: 45-48. PDF